Q&A | WASTE

A shifting landscape for the politics of waste

With China’s ban on waste imports and Malaysia’s return of contaminated plastic waste, the world, and the West in particular, is facing serious questions around the export of waste. Callum Tyndall talks to Peter Jones, principal consultant at Eunomia, about the changing sector.

Sustainability continues to rule the headlines as consumers and companies alike seek to reduce their environmental impact. From a regulatory standpoint, governments are slowly moving to establish bolder goals for recyclability and reusability. However, there are still vast amounts of waste to be dealt with and the handling of much of it has historically been passed on to other countries to deal with. The tolerance for such behaviour is starting to change though, with China putting a ban on waste imports at the start of 2018 and countries such as Malaysia returning contaminated plastic waste to the country of origin.

China specifically referred to no longer being the world’s haven for waste and given its prominent role in handling the waste of other countries, the ban was a significant statement. Ideally, it should have prompted far greater self-reflection on how countries deal with waste and their ability to process it within their own borders. While some have no doubt taken this into consideration, the shift in status quo largely seems to have pushed the waste to alternative markets. With the politics around this treatment of waste shifting, however, how long can governments continue to just export their problems?

Callum Tyndall:

What is the current state of waste importation/exportation?

Peter Jones, principal consultant at Eunomia

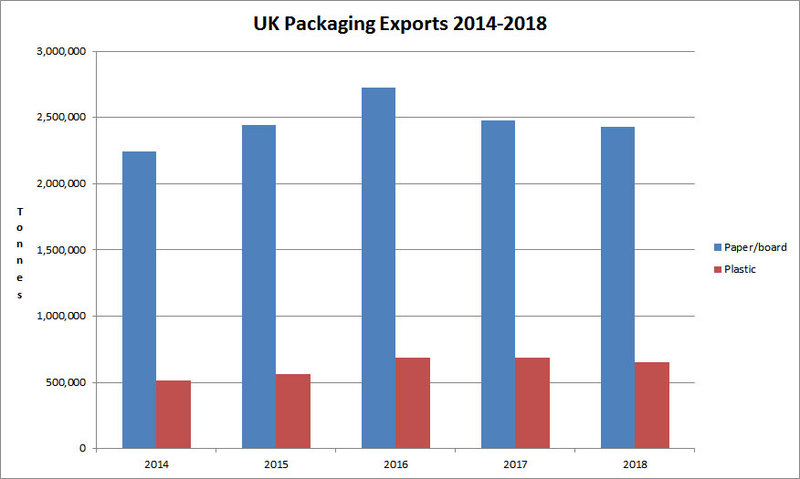

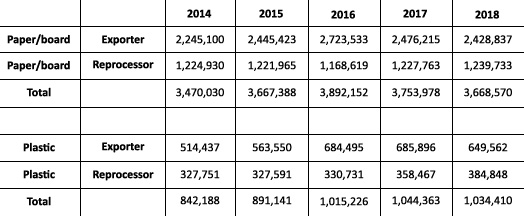

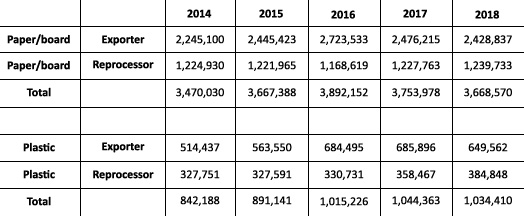

The latest data I have is from the National Packaging Waste Database (so based on PRNs [packaging recovery notes]/PERNs [packaging export recovery notes]) covering the two main materials affected by the restrictions paper/board and plastics:

As confirmed in the table below, there’s been a small increase in domestic reprocessing, mostly offsetting the small decrease in exports. But overall, for the last full year for which we have data, the disruption to the export market doesn’t seem to have translated into any substantial decrease in exports.

There’s no indication of any major change in the first quarter of 2019.

How have changes in policy from countries such as China and Malaysia affected the sector?

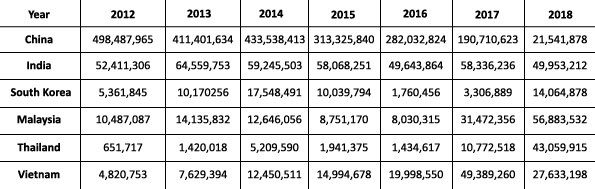

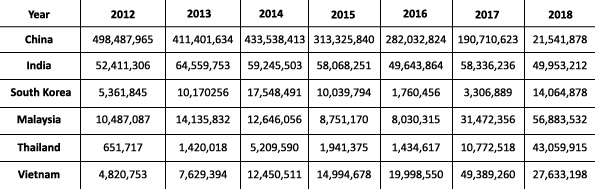

In response to China’s restrictions, the waste sector has sought alternative markets. China was a huge part of the market for both plastic and paper/board.

Replacing that large a share of the export market has been a challenge, and it’s remarkable that new markets were able to be found without more disruption. The US seems to have fared worse in finding export markets – US Commerce Department data indicates that exports have reduced considerably.

It’s difficult to obtain real-time data on where material is now going from the UK, but the concern is that some of the countries may be less capable of managing the export material to high environmental standards than was China. That shouldn’t happen – the UK requires exporters to gather evidence that receiving firms treat waste under “broadly equivalent conditions” to those in the EU – but clearly that doesn’t always prevent questionable exports.

One result of the switch to new, less well-equipped markets could be that concerns arise quite quickly in those countries, and new restrictions appear quite quickly once imports ramp up beyond the local industry’s ability to manage it. So while the sector has been able, for the most part, to manage to keep exports moving and maintain similar prices, that may not continue. However, there are investments taking place in some of those new markets to increase their ability to manage wastes to a high standard.

How is the regulatory landscape changing around waste?

The key regulatory changes that affect the management of waste plastics are the new recycling targets that will boost the tonnage of material that needs to be reprocessed, and the new extended producer responsibility rules that will give producers of packaging the financial responsibility for meeting their targets. These derive from the EU’s revised waste framework directive, but it seems the UK will adopt them regardless of Brexit. The EU is also proposing new, stricter rules on how countries measure how much material has been recycled – which could impact on how attractive exports are.

What is the potential economic impact of this changing landscape?

The key impact of the changes in regulation will be that the cost of managing waste will become a bigger part of the cost that companies incur when they put packaging on the market. If they can find ways to reduce unnecessary packaging, to increase recyclability and raise the value of recyclate, that will reduce the net costs they incur in fulfilling their new legal duties.

The stricter measurement rules – assuming the UK adopts them – will tend to remove a benefit that exports currently enjoy. Although they may contain contamination, they attract export recovery notes as if the whole consignment was the target material – and the whole lot tends to get counted towards recycling. In future, the PRN system seems set to disappear, and recycling will have to be calculated net of all losses through to their entry into the final recycling process.

What is the future of the sector?

That’s a big question. Hitherto, export has offered a cheap option to deal with recyclate that contains contamination. The new system, if properly implemented and enforced, would increase the incentives to reprocess waste within the UK (or at least in the EU, depending on the outcome of Brexit). Enforcement has certainly been an issue up to now, although the Environment Agency talks up the action it is taking.

We’ve already seen Veolia, Biffa and Viridor announce investments in new plastics facilities, increasing the UK’s ability to derive economic value – and jobs – from waste.

After the financial issues suffered by the last generation of specialist plastics recyclers - EcoPlastics, Closed Loop - it is very encouraging to see most of the biggest waste management firms putting money into this area. There is a major opportunity to close the loop and extract more of the value of waste in the UK; then rather than exporting our problematic material abroad, material we may still need to sell elsewhere for it to feed into production will more consistently be a genuine resource.

All data courtesy of Eunomia.

Sustainability continues to rule the headlines as consumers and companies alike seek to reduce their environmental impact. From a regulatory standpoint, governments are slowly moving to establish bolder goals for recyclability and reusability. However, there are still vast amounts of waste to be dealt with and the handling of much of it has historically been passed on to other countries to deal with. The tolerance for such behaviour is starting to change though, with China having banned waste imports from the start of 2018 and countries such as Malaysia returning contaminated plastic waste to the country of origin.

China specifically referred to no longer being the world’s haven for waste and given their prominent role in handling the waste of other countries, the ban was a significant statement. Ideally, it should have prompted far greater self-reflection on how countries deal with waste and their ability to process it within their own borders. While some have no doubt taken this into consideration, the shift in status quo largely seems to have pushed the waste to alternative markets. With the politics around this treatment of waste shifting however, how long can governments continue to just export their problems?

Callum Tyndall:

What is the current state of waste importation/ exportation?

Peter Jones, Principal consultant at Eunomia

The latest data I have is from the National Packaging Waste Database (so based on PRNs [packaging recovery notes]/PERNs [packaging export recovery notes]) covering the two main materials affected by the restrictions paper/board and plastics:

As confirmed in the table below, there’s been a small increase in domestic reprocessing, mostly offsetting the small decrease in exports. But overall, for the last full year for which we have data, the disruption to the export market doesn’t seem to have translated into any substantial decrease in exports.

There’s no indication of any major change in the first quarter of 2019.

How have changes in policy from countries like China and Malaysia affected the sector?

In response to China’s restrictions, the waste sector has sought alternative markets. China was a huge part of the market for both plastic and paper/board.

Replacing that large a share of the export market has been a challenge, and it’s remarkable that new markets were able to be found without more disruption. The US seems to have fared worse in finding export markets – US Commerce Department data indicates that exports have reduced considerably.

It’s difficult to obtain “real time” data on where material is now going from the UK, but the concern is that some of the countries may be less capable of managing the export material to high environmental standards than was China. That shouldn’t happen – the UK requires exporters to gather evidence that receiving firms treat waste under “broadly equivalent conditions” to those in the EU – but clearly that doesn’t always prevent questionable exports.

One result of the switch to new, less well-equipped markets could be that concerns arise quite quickly in those countries, and new restrictions appear quite quickly once imports ramp up beyond the local industry’s ability to manage it. So while the sector has been able, for the most part, to manage to keep exports moving and maintain similar prices, that may not continue. However, there are investments taking place in some of those new markets to increase their ability to manage wastes to a high standard.

How is the regulatory landscape changing around waste?

The key regulatory changes that affect the management of waste plastics are the new recycling targets that will boost the tonnage of material that needs to be reprocessed, and the new extended producer responsibility rules that will give producers of packaging the financial responsibility for meeting their targets. These derive from the EU’s revised waste framework directive, but it seems the UK will adopt them regardless of Brexit. The EU is also proposing new, stricter rules on how countries measure how much material has been recycled – which could impact on how attractive exports are.

What is the potential economic impact of this changing landscape?

The key impact of the changes in regulation will be that the cost of managing waste will become a bigger part of the cost that companies incur when they put packaging on the market. If they can find ways to reduce unnecessary packaging, to increase recyclability and raise the value of recyclate, that will reduce the net costs they incur in fulfilling their new legal duties.

The stricter measurement rules – assuming the UK adopts them – will tend to remove a benefit that exports currently enjoy. Although they may contain contamination, they attract export recovery notes as if the whole consignment was the target material – and the whole lot tends to get counted towards recycling. In future, the PRN system seems set to disappear, and recycling will have to be calculated net of all losses through to their entry into the final recycling process.

What is the future of the sector?

That’s a big question. Hitherto, export has offered a cheap option to deal with recyclate that contains contamination. The new system, if properly implemented and enforced, would increase the incentives to reprocess waste within the UK (or at least in the EU, depending on the outcome of Brexit). Enforcement has certainly been an issue up to now, although the Environment Agency talks up the action it is taking.

We’ve already seen Veolia, Biffa and Viridor announce investments in new plastics facilities, increasing the UK’s ability to derive economic value – and jobs – from waste.

After the financial issues suffered by the last generation of specialist plastics recyclers - EcoPlastics, Closed Loop - it is very encouraging to see most of the biggest waste management firms putting money into this area. There is a major opportunity to close the loop and extract more of the value of waste in the UK; then rather than exporting our problematic material abroad, material we may still need to sell elsewhere for it to feed into production will more consistently be a genuine resource.

Peter Jones

Principal consultant at Eunomia

Website:www.eunomia.co.uk